I’ve been writing true crime for 10 years. I confess to occasional pangs that I am reopening wounds for a few people, but the old-school journalist in me rationalizes that these stories can have a universal, positive, human impact to the greater society. Whether they reflect something in us that we should (and don’t want to) acknowledge, or simply display the worst extent of human behavior, there seems to be a higher calling for true-crime storytellers, even if it occasionally gets lost in the bloody, exploitive, exhaustively grotesque din of … true-crime storytellers.

I have long seen my genre as two sub-genres: the commercial and the literary.

Bonnie & Clyde’s death scene.

You find commercial true-crime on supermarket shelves, usually paperbacks with blood-spattered covers and the word “fatal” somewhere in the title. These are fan favorites, usually about ordinary crimes, told in formulaic prose that follows a familiar beat: crime, investigation, arrest, trial, conviction, and if required, execution. Usually a female victim or two (although occasionally an unlikeable female perp), a resolution, and then the bad guy gets what’s coming to him.

Literary true-crime books delve deeper (and sell less briskly) as they chart a more philosophical and poetic course into the darkest corners of human behavior. (That can piss off the commercial true-crime reader who wants no poetry, no philosophy, no dawdling.) Theese include Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and James Ellroy’s My Dark Places.

Personally, I believe we should do more of these deeper examinations of human behavior, although I cannot kid myself that the reading/listening/viewing public doesn’t want to work that hard. The salacious sells. Always has. Always will.

But does the texture of the literature matter? Recently, Rachel Chestnut, a 17-year-old student, asked an intriguing question in a New York Times essay: Is true crime as entertainment morally defensible?

“Unfortunately … advantages are outweighed by the genre’s tendency to exploit suffering, lean toward a preconceived narrative, prioritize ratings over morality and manipulate public opinion,” Rachel wrote.

“victims and their families have no real way to opt out of media coverage … For the sake of the perfect murder story, tragedy is ruthlessly dissected in the limelight without considering those actually affected. Although the coverage of crimes often converts them to tales for public consumption, the prolonged suffering of these victims is gut-wrenchingly real, yet often forgotten by engrossed viewers. … [and] the true crime genre is inescapably prone to subjectivity.”

The kid is right.

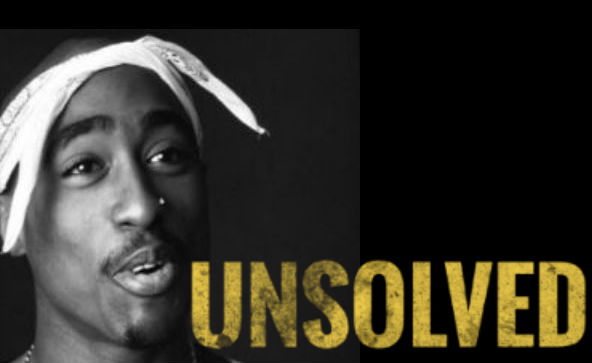

If you don’t think so, just witness the explosion of true-crime podcasts and TV series, from a dramatic TV rendition of the Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls murders to the vaguely discomfiting www.MyFavoriteMurder.com, a podcast for aimed squarely at homicide cult-girls. (It’s OK if you take a moment to shudder. I’ll wait.)

So while I genuinely believe true-crime storytelling has a place in our literature, I think some of it—mostly in the hands of wild-eyed TV producers, home-radio amateurs, and wannabe writers who self-publish—has gone too far. And I’m not alone.

“The true crime genre has the potential to open minds and act as a public judicial review,” the young and smart Rachel says, “but in order for it to successfully do so, it must abandon the sensationalisation of tragedy for entertainment’s sake.

“Otherwise, its inherent flaws overshadow any possible benefits. Additionally, viewers must remain conscious of what they consume and never accept subjective interpretations as indisputable fact.”