Twenty years ago, in 1999, the Chicago Sun-Times’ legendary book editor Henry Kisor—who had fallen in love with my first novel Angel Fire—asked me to be one of 10 American authors who, upon the centennial of Ernest Hemingway’s birth in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, would write about Papa’s life and influence. I was 42 when I wrote the following essay about For Whom the Bell Tolls for the Sun-Times. At the time, I’d written only two novels and was writing a third (that still sits unfinished in my trunk). Today, 20 years beyond, I have written 17 books, Hemingway would certainly be dead by now if he hadn’t killed himself, and what I know for sure about Papa is that he’s unknowable … and I’m okay with that

BY RON FRANSCELL

June 6, 1999 © Chicago Sun-Times

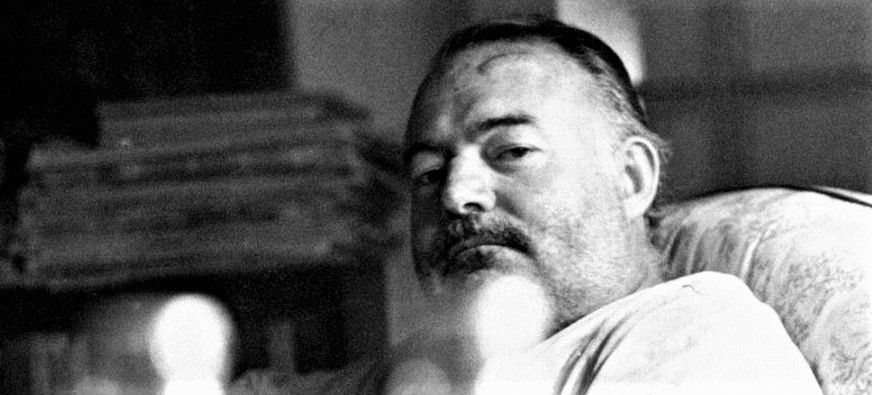

Ernest Hemingway haunts me.

Perhaps not the same way that he haunts you. After all, his ghost has published nearly as many novels since his death as the flesh-and-blood Papa. Thirty-eight years since he disintegrated whatever great untold stories remained in his brain, we cannot escape the stories that remained in his trunk.

But my haunting is different. Papa’s spirit has stalked me throughout my career as a newspaperman and novelist. His bust, a gift from a college teacher who understood my admiration, sits on the shelf above my writing desk, literally watching over me. I worked one summer as a newspaper intern in the small town where he started A Farewell to Arms—then took my first reporting job in another small town where he finished it. I still shadow-box with his muscular prose, forged in the furnace of a newsroom, and hammered thing and razor-sharp in his later work. One true sentence would keep him writing, he said once. One true sentence.

For Whom the Bell Tolls was the first Hemingway I ever read. I was a high school kid in the early 1970s, working on my campus newspaper, newly graduated from Jack London but not yet ready for Jack Kerouac.

To my young eyes, it was just a good action story: Robert Jordan, a passionate American teacher, joins a band of armed gypsies in the Spanish Civil War. He believes one man can make a difference. The whole novel covered just 68 hours, during which Jordan must find a way to blow up a key bridge behind enemy lines. In that short time, Jordan also falls in love with Maria, a beautiful Spaniard who has been raped by enemy soldiers.

The whole spectrum of literature was refracted through the prism of my youth: Good guys and bad guys, sex and blood, life and death. For me, just a boy, the journey from abstraction to clarity was only just beginning.

Re-reading For Whom the Bell Tolls at 42 (roughly the same age Hemingway was when he published it) I have lost my ability to see things clearly in black and white. My vision is blurred by irony, as I note that two enemies—the moral killer Anselmo and the sympathetic fascist Lt. Berrendo—utter the very same prayer.

For the first time, I see that the book opens with Jordan lying on “the pine-needled floor of the forest,” and closes as he feels his heart beating against “the pine needle floor of the forest.” Jordan ends as he began, perhaps having never really moved.

I certainly could never have grasped at 16 how dying well might be more consequential than living well. And somehow the light has changed in the past 26 years, so that I now truly understand how the earth can move.

As a teenager I missed another crucial element, even though Vietnam was still a seeping wound. Three pivotal days in Jordan’s life force him to question his own role in a futile war. He wonders if dying for a political cause might be too wasteful, but he ultimately concludes that dying to save another human is a man’s most heroic act.

The book’s title is taken from John Donne’s celebrated poem: “No man is an Iland … and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee.” It was not about loneliness or aloneness, but about the seamless fabric of all life: What happens to one happens to all.

“It was as though you had thrown a stone and the stone made a ripple and the ripple returned roaring and toppling as a tidal wave,” Hemingway wrote about the battle in the final chapter. But the ripples surround more than war—although the theme has certainly lurked in American policies about falling dominoes in Southeast Asia and ethnic cleansing in the Balkans—but also the whole house of cards called human interaction. One small act has momentous consequences.

Although Papa has watched me write two novels, and the themes of For Whom the Bell Tolls echo now in my third, I am not blind to Hemingway’s flaws. He was a good short story writer, and what was short was almost always better. Hemingway is at his best in leaner, self-contained sequences. Pilar’s tale on the mountainside has been acclaimed as the most powerful of Hemingway’s prose. Her story within a story is nothing less than a modern myth.

But For Whom the Bell Tolls has also been regarded as Hemingway’s capitulation to critics who barked that his innovative style was too lean, and as a consciously commercial exercise for which Hollywood might (and did) pay handsomely. And although he was a founding member of the indulgent and disenfranchised “Lost Generation,” Hemingway is too politically incorrect for most of today’s genteel rebels.

Hemingway is now a ghost shrouded in his own myth. But he still haunts many of us who have struggled to find clarity in stories men have told for millennia. It is not his personal myth that should move us, but his place in our mythology. Robert Jordan, in so many respects, was a tragic mythical hero in the vein of Achilles, Gawain, and Sampson. For Whom the Bell Tolls ranks as one of the great American war novels in a century that has always struggled with the concept of good and bad wars.

And Hemingway understood what every good storyteller from Homer to Hillerman has known: There’s a rhythm that resonates deep inside, deeper than any big, two-hearted river. But Hemingway would have brushed off such ruminations.

“It is all very well to write simply,” he told young writers, “but do not start to think so damned simply. Know how complicated it is, then state it simply.”

One true sentence.