My son’s eyes brightened when he saw his new baseball glove.

He was about to start a sort of pre-school for Little Leaguers, and he buried his face in the smell of new leather. He’s only 4 and he’s only tossed a ball in the backyard, but his very own glove was too much.

“I love baseball,” he said. I laughed.

He delights in the game, as if it were born in him. He even has a pretty good arm for a 4-year-old. Maybe it was born in him.

MY GRANDFATHER, a Missouri sharecropper, played town-team ball in the dusty days of the Depression. He was a wiry boy in his late teens who left the field at the end of the week to play ball on a team that sometimes walked to nearby towns every weekend. Their games were attended by the local farmers’ daughters, and among them was the one who’d become my grandmother.

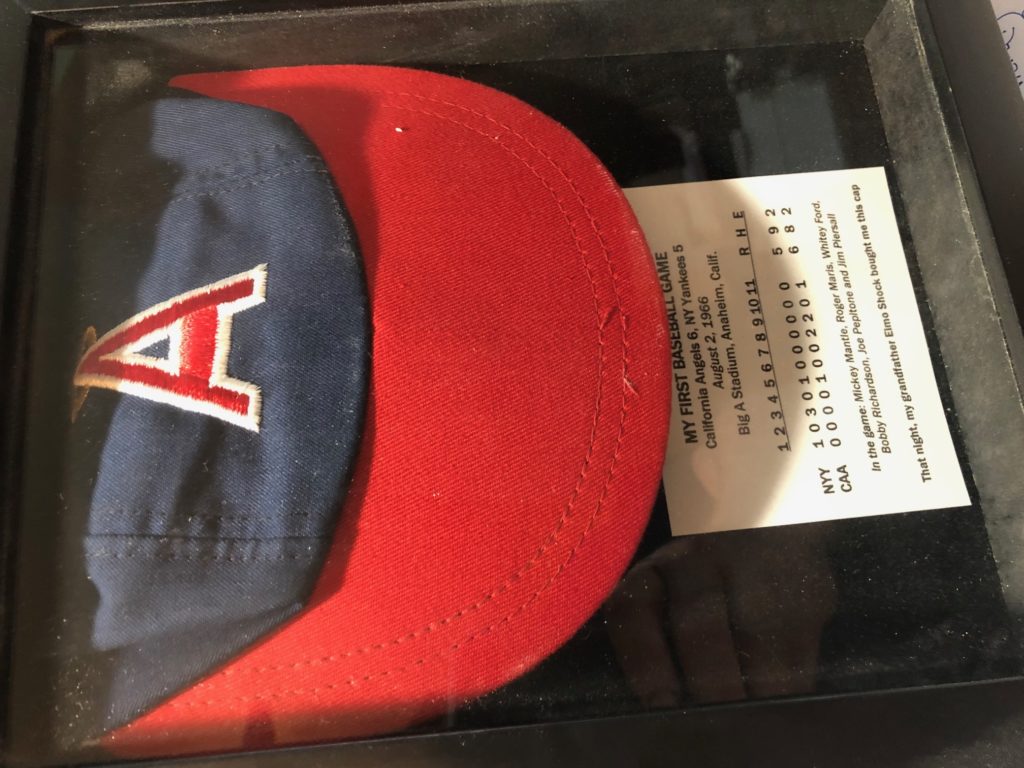

It was my grandfather who took me to the first professional baseball game I ever saw. I got a glimpse of the last golden days of Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, and Roger Maris—all in separate states of decline in the summer of ‘66—as the Yankees lost the California Angels in extra innings. He bought me a cap and a hotdog. I was only 8, but from where we sat just off the first-base line, I saw instantly I’d always love baseball, too.

A few days later, my grandfather bought me my first real leather glove, a Willie McCovey model slightly too big for my little hand. We sat on the back porch as he rubbed and coaxed it with Neatsfoot oil, making the pocket as soft as outfield grass while he told me stories about his long-ago days playing ball in Missouri summers. As he spoke, he seemed to go back there.

It wasn’t just baseball he missed. It was his Missouri roots, too. He eventually left his farm and his baseball to make his way as a factory worker on the West Coast. He’d spend some Saturdays at the ballpark, a spectator, not a player. I still marvel at his uncanny ability to watch the Angels on TV while listening to a Dodger game in his transistor-radio earpiece.

The next season in Little League, I hit my first home run. Not one of those five-error, inside-the-park bag cleaners, but an honest-to-God over-the-fence homer. They gave me the ball and life was good—until the next game when I struck out three times swinging for the fences. I wanted so badly to give my second-ever home-run ball to my granddad, an even trade for what he’d given me.

Ten summers later, my grandfather died. My hand had long since grown into my Willie McCovey. I was playing my first and only season of semi-pro ball, my last summer of organized baseball.

In that twilight of dusty roads and fresh-sprinkled grass, my life connected with my grandfather’s in a way I never really understood before. In the oiled, brown leather of my old glove, my grandfather’s memories were preserved and my hand fit perfectly there.

I SAT ON THE FLOOR with my own son last weekend, coaxing and rubbing his new Ken Griffey Jr. glove with Neatsfoot oil, telling him stories about games won and lost a long time ago. I told him, as simply as I could, that his great grandfather was a baseball player, too.

Maybe he loves baseball in a different way than his dad. Like so many things a 4-year-old sees, it’s just a happy adventure without an ending.

And his Ken Griffey Jr. glove is more than a tad big for his little hand, but in a few summers, softened with more Neatsfoot and even more memories, it will fit as it should.

“Why do we rub oil on it, dad?” he asked me.

“So it will be soft,” I told him, “and so you’ll have it for a long time.”

This essay was first published in 1991. Soon, I hope to talk to my 5-year-old grandson about baseball, memories, and his great-great grandfather. And maybe there’ll be a glove involved.