The term “murderabilia” was coined by my friend Andy Kahan, who advocates for crime victims for Crimestoppers of Houston. But the word is actually more innocuous than Kahan’s feelings about the weird, lurid, and occasionally baffling crap that true-crime collectors covet.

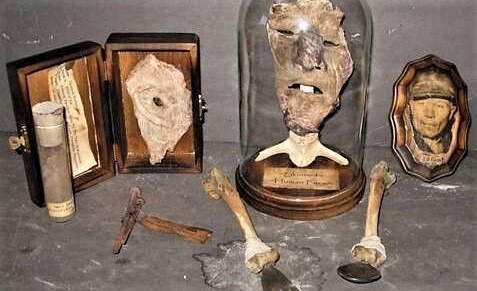

In recent years, for example, you could buy a serial killer Angel Resendiz’s foot scrapings for $75—although inflation might have pushed them to $100 now. Charles Manson’s half-eaten bag of Reese’s Pieces was $425. The gun that killed Trayvon Martin might have been auctioned for $250,000. An empty aspirin tin found on the floor of Bonnie and Clyde’s death car sold for $11,400. A painting by serial killer John Wayne Gacy of the Seven Dwarves playing the Chicago Cubs once went for $9,500. A paper towel never used by Manson? Priceless.

Kahan has been a crusader against this garbage. “Murderabilia glorifies violent crime and causes the loved ones of victims undue pain,” he told Huffington Post in 2012, when he’d already been crusading against it for 20 years.

But now, in a spurt of true-crime popularity that’s caused Hollywood, podcasts, and some books to go to exploitive and macabre extremes to grab your clicks and eyes (“My Favorite Murder” podcast, for instance), someone has fashioned a whole podcast around murderabilia to explore some collectors’ fascination with letters, bodily fluids, trash, clothing, and other rubbish generated by infamous (and some unheard-of) killers.

Comes now “Murderabilia,” a podcast that will be available in the USA soon. It explores those odd fanatics who gobble up items killers sell —fingernail clippings, for God’s sake!—for pocket money.

Its producers Alice Fiennes and Poppy Damon recently told CNET they’ll explore some of the weird items that true-crime wackos trade, who profits, the ethics of the grim commerce of violent death, and whether it’s even acceptable to collect it.

“I started off thinking this subculture had little to do with true crime and ended up thinking it had everything to do with it,” Damon said. “I think it is all part of the same mystique. Many of us collect gruesome stories and most of us keep some kind of souvenirs from important events (gruesome or not). I’ve ended up feeling it’s not so weird to combine these things.

“Superstition is something so built into our history. Murderabilia is all about connecting with darkness—you can get a buzz off it … it’s a form of thrill seeking.”

For their program, Fiennes and Damon actually purchased an authentic letter written by killer Sean Sellers.

“I felt quite conflicted about buying an item at first, knowing that we would be paying money into a machine that, in turn, pays out to killers in prison,” Fiennes said. “But, in the end, time and the specific origins of our piece of murderabilia neutralized those feelings of conflict.”

Insofar as Murderabilia, the podcast, explores the freakishness of this hobby, it is not an unworthy addition to today’s true-crime cacophony. As long as it can roll its eyes at some of these obsessive geeks, it might have value. If it can truly add to our understanding of the minds the fixated “fan,” why not?

Is memorabilia associated with the murders of Lincoln or Kennedy not historic? Should we not preserve and display the shoes of Jews slaughtered by Hitler?

Maybe there’s some historic value to some of this grim stuff, but Charlie Manson’s hair in the shape of a swastika? Maybe not.

If and when Murderabilia becomes the demented audio version of Antiques Roadshow for abnormal traders of John Wayne Gacy’s garden shovel or Jeffrey Dahmer’s freezer door, it will deserve a shallow grave where the headstone is routinely stolen by crime freaks.

Bestselling crime writer Ron Franscell is the author of “Alice & Gerald: A Homicidal Love Story“ and “The Darkest Night.” He owns nothing of macabre value.