Just days after 9/11, the Denver Post dispatched me to the Middle East to cover the new War on Terror from the front lines. But I had another mission: to seek answer to a question we were all asking … Why us?

The author in the Sahara after 9/11

Ultimately, I served two tours over there. During the first, I was embedded aboard the USS Enterprise as the American military launched sortie after sortie around the clock, to “re-arrange the rubble in Afghanistan,” as one Marine fighter pilot told me. After that, I joined Allies in the Sahara as they prepared for the ultimate invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, then briefly a Ranger unit in Pakistan.

But most days, then weeks, I wandered the streets of Cairo, Khartoum, Damascus, Beirut … and any other Arab or Muslim capital that would allow me past customs (only Tehran didn’t), asking that one haunting, essential question in a thousand different ways … Why us?

Then Wall Street Journal reporter Danny Pearl was beheaded by al Qaeda. Many news outlets, including the Denver Post, frantically recalled their reporters. So, I boarded a plane in Cairo, laid over in London, then began the long flight home.

I don’t sleep well on planes, and after 9/11, I could sleep not at all. There in the dark, one of only a few passengers brave enough to fly, a thousand miles in the night and a million miles from where I belonged, I was exhausted. So, I rifled through some news magazines. One was a French weekly. I couldn’t read French so I just looked at the pictures, only half-awake, half-caring, and half-seeing.

But one of them snapped me out of my fog. It showed two people plunging from the burning World Trade Center—holding hands.

I’d never seen such an image. It punched me deep in my gut. These two people had chosen between two different kinds of death, but each comforted the other as they died together—holding hands.

Instantly, I was in a different moment that really never happened except in my memory when I was just a kid in 1973. It wasn’t a proper memory, but an image: Two girls falling from a very high bridge into a very deep, dark canyon in a secret corner of Wyoming—holding hands.

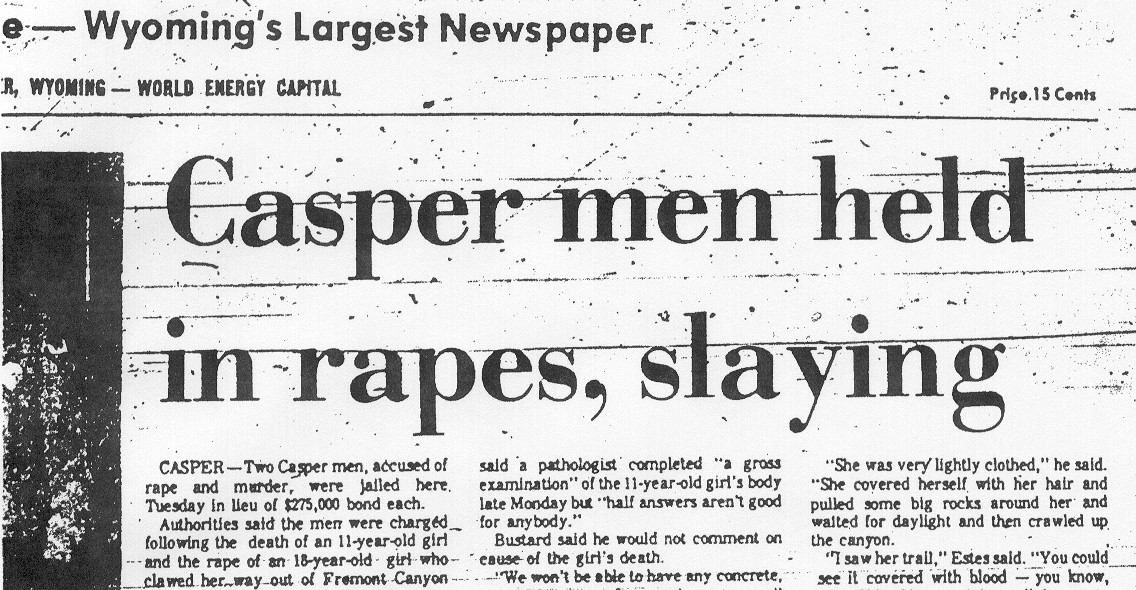

They were two sisters, literally the girls next door who were abducted, terrorized, one of them raped, and both thrown from a bridge in the heart of nowhere. Amy and Becky had, in fact, been thrown at different times and could not have held hands as they fell, but being sisters who shared the horror, I imagined them that way. One died and one lived … and I didn’t know the rest of their story.

They were two sisters, literally the girls next door who were abducted, terrorized, one of them raped, and both thrown from a bridge in the heart of nowhere. Amy and Becky had, in fact, been thrown at different times and could not have held hands as they fell, but being sisters who shared the horror, I imagined them that way. One died and one lived … and I didn’t know the rest of their story.

September 11, 2001, changed everyone’s world. September 24, 1973, changed my world first.

There in the dark lost and tired, I knew I would tell their story.

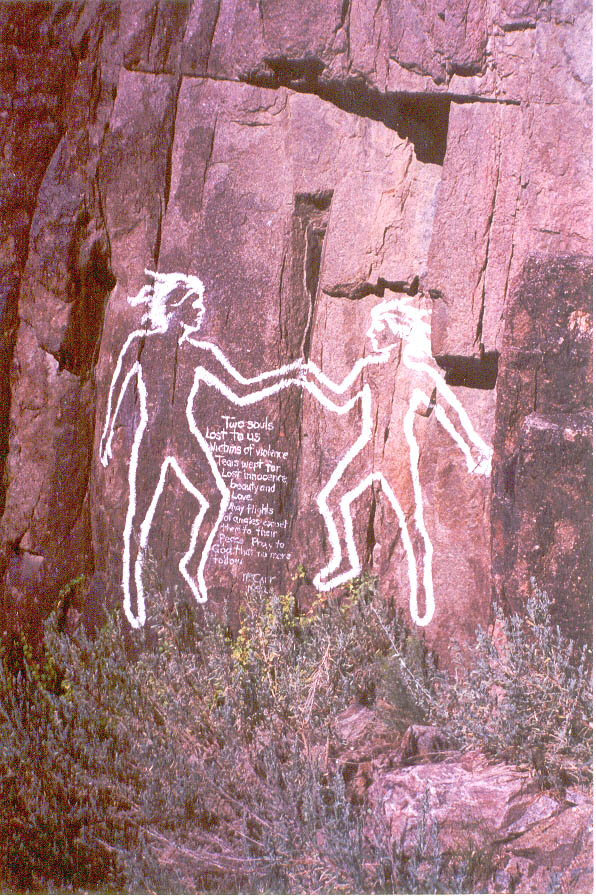

Back home, after a few days of rest to regain my equilibrium, I went back to Wyoming to visit the places where the crime had unfolded, including the canyon where the incalculable horrors had happened. Years later, the bridge was still haunted. And sometime in there, a local guy had painted on the canyon wall the outlines of two young girls, falling from a mythic height—holding hands.

Pictograph at the bridge

I’d covered a war but this bridge—or the memory of this bridge— made death real to me. I didn’t think of myself as immortal or indestructible, but until that day, I hadn’t really considered the finality, the absolute black vacuum, of dying. Suddenly, I was afraid of it, and I still am.

So, I did what people like me do when they are angry, sad, confused: I wrote a book about it, The Darkest Night.

All of us are haunted by 9/11, but that’s how 9/11 haunts me. The WTC attack, wading around in a foreign place asking why, Amy and Becky holding hands, how everything changes and we lose pieces of ourselves … no anniversary passes that it isn’t all tangled up. But what choices do we have?

I’m older now, closer to the end than the beginning. Maybe I knew how I’d feel now when I wrote at the end of The Darkest Night:

Survival is an instinct, not a choice. Perhaps Becky’s courage came from fear: She was afraid to die. Her only hope — hope distilled to its ethereal essence — was the very next breath. Not tomorrow. Not next week.

Maybe solid ground is just an illusion. We want to feel the earth beneath our feet, to dig our toes deep in it, to stand up on our own while we touch someone.

But will we all fall eventually? If, like gravity itself, evil is a force of nature, can we avoid a freefall for a whole lifetime?

Probably not. But we can acknowledge that it’s a messy world, and humans weren’t intended to live behind stone walls, so we must find our place in our messy world … or not truly live at all.

Ron Franscell is a journalist and crime writer. The Darkest Night (2007, St. Martin’s Press) was his first nonfiction book and was hailed by true-crime icons Ann Rule and Vincent Bugliosi as a direct descendant of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.