I never met Elsie Mae but I wish I had.

I don’t know too much more than last week’s obituary tells me: She taught grade school for most of her life, led Sunday school, and played the church organ at the First Presbyterian Church in Ottumwa, Iowa. She had 13 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. She wrote poetry, even a little history book, but most of all she loved to read. She was 86 when she died, so I know she had a lot of stories to tell.

One of her daughters went home to Iowa for the funeral and, sadly, to put Elsie Mae’s things in order. One chore was digging through a mountain of her books. Elsie Mae kept notes as she read, jotting down a word that made her smile, or something she wanted to think about a little more. Many of the books contained margin notes here and there, an index card, maybe a few sticky notes to mark pages she’d want to read again.

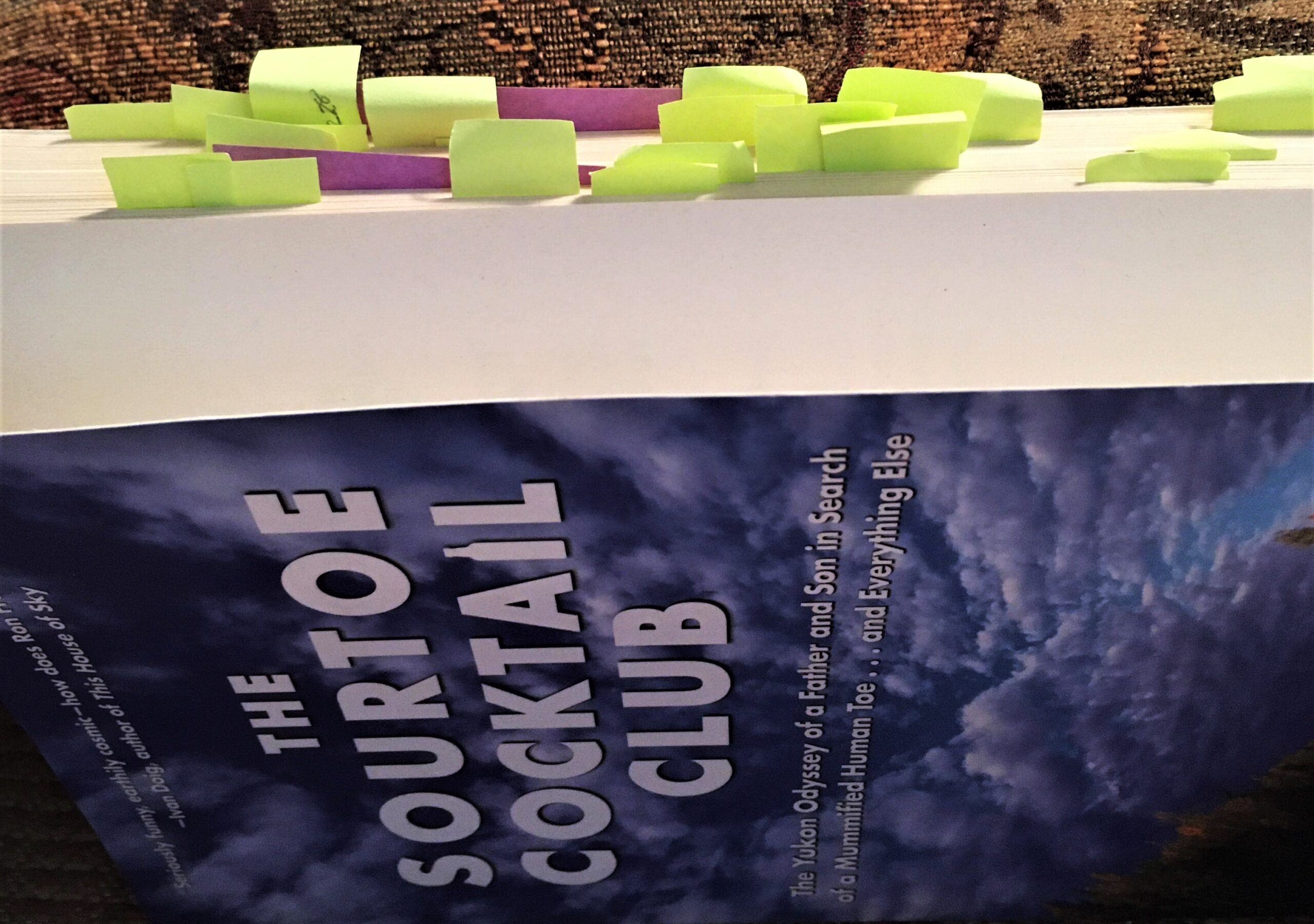

But one book stood out like a Post-it bouquet. So many pages were flagged that Elsie Mae might just as well have revisited a random page to find the word or idea that excited her enough to mark it in the first place. And she’d made notes in a spiral notebook, too.

It was “The Sourtoe Cocktail Club,” my 2011 memoir about a magical trip with my teenage son to the Yukon to find a legendary cocktail containing a mummified human toe. It wasn’t so much about the Toe, but more about a recently divorced dad wanting to make sure he was still relevant to his son. I consider it my best book.

And Elsie Mae loved it, too.

“She was a huge fan,” her daughter texted me, along with images of the exuberantly earmarked book and two pages of handwritten notes Elsie Mae kept. She’d analyzed my book as if to write a graduate dissertation or pulling a caffeinated all-nighter before the midterms. But she wasn’t. She was simply finding the soul of a book she loved.

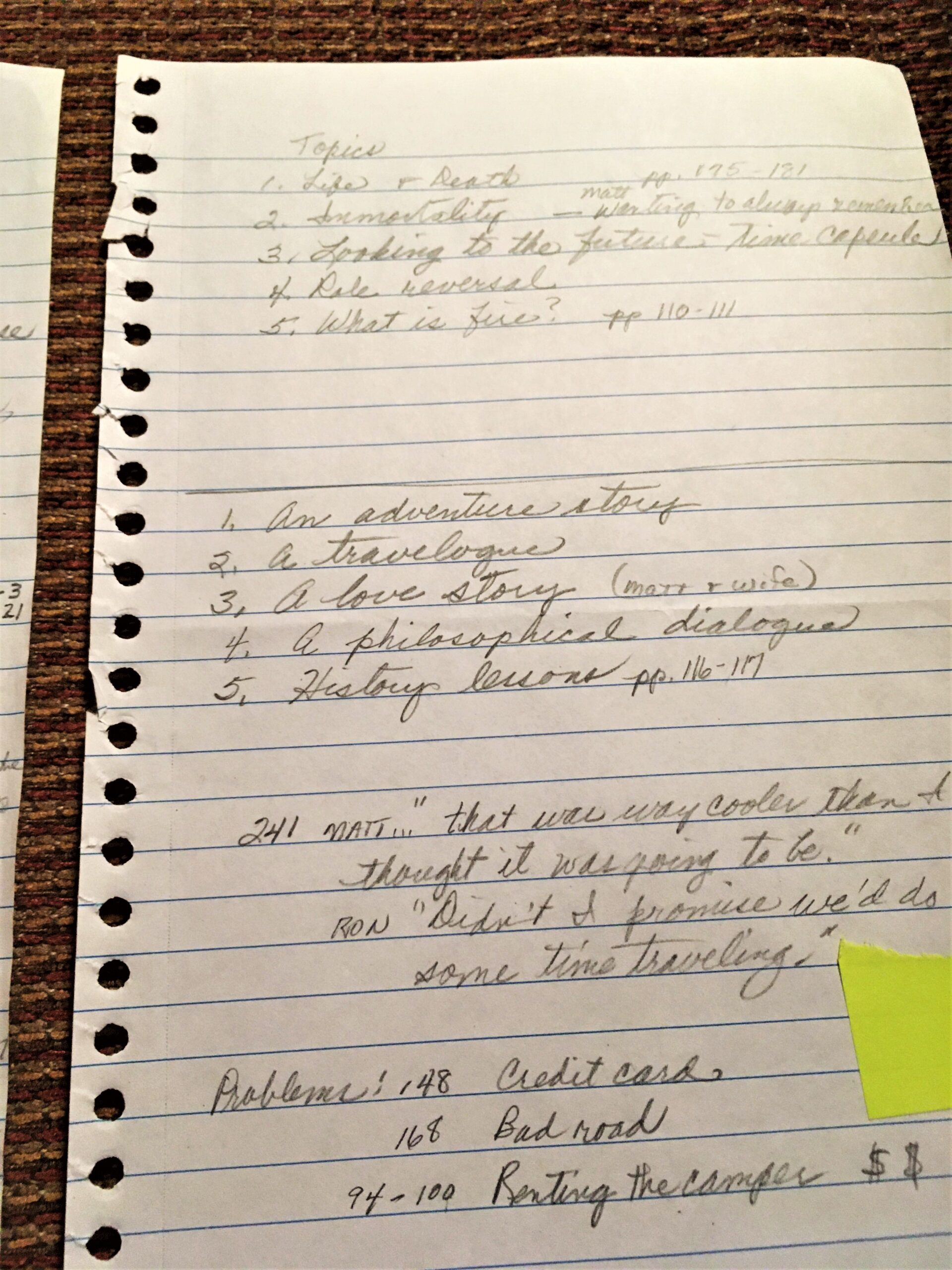

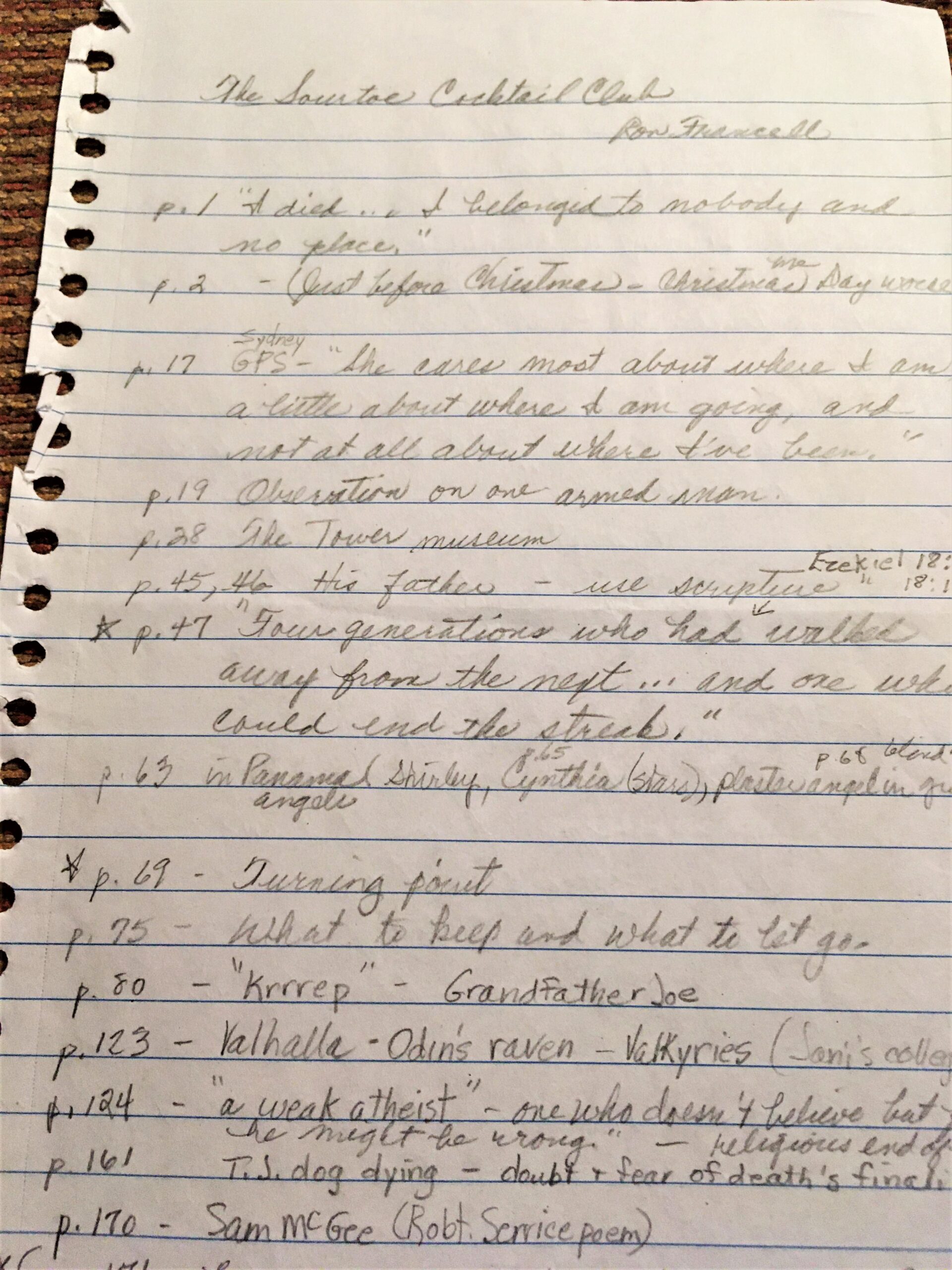

Elsie Mae’s marginalia noted themes of life and death, immortality, hope, role reversal, and the composition of fire.

Elsie Mae’s marginalia noted themes of life and death, immortality, hope, role reversal, and the composition of fire.

She classified “Sourtoe” as an adventure story, a travelogue, a love story, a philosophical dialogue between father and son, and a history book.

Elsie Mae annotated quotes like, “I died … I belonged to nobody and no place” and “Didn’t I promise we’d do some time-traveling?”

She pegged the turning point in the story at Page 69.

And she loved one word that popped up a few times in the arduous journey, my Italian grandfather’s favorite (and heavily accented) cuss word: Krrrep.

As I read Elsie Mae’s notations … as I saw what words stuck to her heart like one of her Post-it notes … as I realized how my words had made her think or smile, I choked up. It wasn’t just that in the Age of Kindle, few readers make notes anymore, nor that I didn’t think words mattered. It was that I utterly underestimated how much my words mattered to at least one reader.

As I read Elsie Mae’s notations … as I saw what words stuck to her heart like one of her Post-it notes … as I realized how my words had made her think or smile, I choked up. It wasn’t just that in the Age of Kindle, few readers make notes anymore, nor that I didn’t think words mattered. It was that I utterly underestimated how much my words mattered to at least one reader.

On any given day I might be writing for entertainment, for money, for art, or just to chase away some shadow that haunts me at night. I always imagine the arrangement of my words matters to me more than it does to you. But it mattered to Elsie Mae more than most.

It’s a gift to be reminded, even if only once in a lifetime, that somebody out there—somebody you never met—can be especially moved by the way you arrange those words.

Godspeed, Elsie Mae.