WARNING: Some morgue and crime-scene photos appear in this essay.

Funny story. Not long ago, I was telling a fascinating little yarn about the autopsy of a deranged killer whose body was riddled with more than 200 bullets after pursuing police cornered him at the end of one of modern America’s bloodiest massacres.

Then my wife nudged me with one of our secret signs that maybe I should change the subject because, after all, we were at a funeral.

John Dillinger

In 30 years as a newspaperman and a couple true-crime projects, I sometimes forget my threshold for grisliness is somewhat higher than the ordinary human’s. I have attended autopsies and exhumations, thumbed through hundreds of coroner reports, pored over grotesque evidence photos, learned a couple cool tricks to keep from retching from death-stink, and seen more than my share of gore-splattered crime scenes. Most times, I know how far is too far, but sometimes I forget that I chose to see these things so you (the common public) didn’t have to … mostly because, trust me, you don’t want to.

Lee Harvey Oswald

This, of course, totally neglects the voyeurism that is such an intimate part of true crime. From graphic descriptions of rape and dismemberment to uncloseted skeletons, many of us want to see the darker elements of crime and punishment.

Honestly, I don’t know which bothers me more.

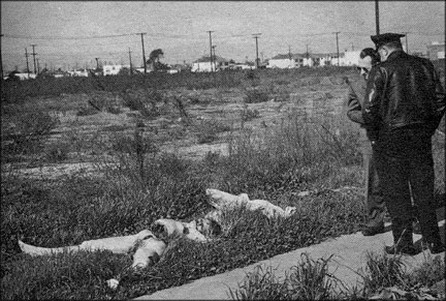

Bonnie & Clyde

I have held forth here and elsewhere in the past that true-crime publishing has become largely pulpy and exploitive, splashing faux blood on bookjackets and promising “16 Pages of Shocking Photos!” I cannot believe that shocking photos are more attractive to true-crime readers than good, dramatic storytelling … but it wouldn’t be the first time I’ve been dead wrong.

One of the classics of the genre is Gary Lavergne’s 1997 Sniper in the Tower, about Charles Whitman‘s 1966 shooting spree from the University of Texas Tower. It set a standard for detailed research and reportage, but more interestingly, its photo insert contained images of Whitman’s dead wife and mother in which their actual corpses were Photoshopped out. Only the blank outline of their bodies remained. While I understand the motivation to show a little dignity in a genre that usually doesn’t, I also felt that someone decided my constitution wasn’t strong enough to see two tiny black-and-white dead people. Run the image or don’t run the image, I thought, but don’t manipulate it.

Bloody crime-scene photos don’t affect me much, but I must realize I’m far more jaded than most. For me, color seems to be more provocative than black-and-white; yesterday’s images are far more affecting than tintypes of Jesse James’ corpse. But in the end, I would neither buy (nor refuse to buy) a book based on my reaction to a surreptitious glimpse of its photos in the checkout line. The images, like the adjectives, just add color to the movie that unreels in my head as I read.

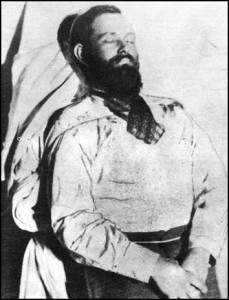

Jesse James

If my wife were here right now, she’d nudge me. She’d remind me that not everyone has inspected, up close, the logo on a dead man’s socks, or seen a dead man’s bloated body burst like a sad balloon on a hot summer afternoon.

And not everyone can come here to ask some of true crime’s most devoted fans how they feel, so … what’s your feeling about disturbing crime photos in true-crime books and magazines? Are they truly off-putting or an essential part of why you read true crime? Will grotesque pictures influence your purchase (or refusal to purchase) a book?