“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

—William Faulkner

So the would-be mass murderer at Ohio State University this week was apparently inspired by the hateful words of American-born cleric Anwar al Awlaki, al Qaeda’s most powerful recruiter before he was obliterated in a US drone strike in Yemen in 2011.

Awlaki’s childhood home in Las Cruces NM

A few years ago, I chased Awlaki’s ghost to the New Mexico town where he was born—Las Cruces—and I stood in front of the Spartan university bungalow where his parents brought the newborn infant Anwar home for the first time. Suddenly, he was not simply a heinous terrorist puppetmaster who existed in some mysterious netherworld … he was, for a fleeting moment, a baby in the arms of a couple college kids who had no idea of the monster he’d someday become.

Seven years ago, I started a series of books called the Crime Buff’s Guides™. They explore the crime history of places like Texas, Pennsylvania, or Washington DC, by pinpointing significant locations with GPS coordinates. Seven Crime Buff’s Guides now exist, and next year, WildBlue Press will publish The Crime Buff’s Guide to Outlaw Los Angeles.

Crime is part of history, part of who we are. So the history of crime is important to understanding our culture. And just like other historic sites where imagination, myth and history entangle, significant outlaw-related sites can also offer a glimpse beneath the surface of the present. As every traveler knows, visiting important—and sometimes forgotten—places can enlarge our understanding of history infinitely.

Why travel thousands of miles to visit sites in the darkest corners of human events? I believe that standing on a historical spot can change your view of history. I’m an old-school newspaperman. I believe there’s something important to be learned from “being there.”

I always imagined JFK’s assassination had been a great drama played out on a great stage—so expansive that one man couldn’t possibly have committed that heinous murder at such a great distance.

Then I visited Dealey Plaza, which was, in reality, much more intimate and small than I imagined. When I peered down on the fateful spot from Oswald’s sixth-floor perch, I realized that any Wyoming kid who ever hunted rabbits with a .22—as I did—could have made that shot. “Being there” changed my whole perspective of that tragic event.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre happened in a Chicago warehouse that’s now a park where children play. The Black Dahlia’s dismembered body was found in an open field that today is somebody’s suburban Los Angeles front yard. Actor Fatty Arbuckle’s debauchery took place in a landmark San Francisco hotel room—which you can still rent today. You cannot know how frenetic the famous gunfight at the OK Corral must have been unless you stand in the claustrophobic alley where the Earps and Doc Holliday stood … and see how their adversaries were so close that you could almost reach out and touch them.

Columbine memorial in Littleton CO

It’s impossible to visit the site of the Columbine mass murder in Littleton, Colorado, and not be moved. It’s impossible to stand in Ford’s Theatre and not feel surrounded by ghosts. And it’s impossible to visit the crumbling site of the famous Chicken Ranch—“the best little whorehouse in Texas”—and not smile.

But many of my favorite places have told very human stories. There’s a cemetery in Texas where the patriarchs of two feuding families, killed by each other in a fatal barroom brawl, are buried side-by-side and (by order of the sheriff) their two graves have been literally chained together for eternity.

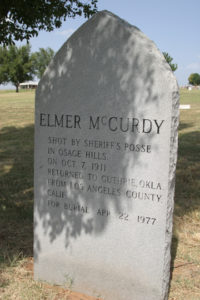

McCurdy’s final-final resting spot

Then there’s the strange tale of small-time Oklahoma outlaw Elmer McCurdy, shot down by a posse in 1911. When nobody claimed his body, the local undertaker mummified him and displayed his corpse until a few years later when some outlaw cohorts claimed the body—and promptly sold it to the carnival circuit. Elmer’s body was a midway attraction for decades, then disappeared. In 1976, a TV crew filming a “Six Million Dollar Man” episode in a deteriorating Los Angeles amusement park found a mannequin in a warehouse. The mannequin turned out to be Elmer’s mummified corpse. He was returned to Oklahoma and buried under two tons of concrete—so he’d never be moved again.

And in the sleepy town of Granbury, Texas, where men claiming to be John Wilkes Booth, Jesse James and Billy the Kid showed up—long after they were all presumed dead.

In the small, overlooked stories, I often find the kind of human stories that make it all worthwhile.

Explore all the CRIME BUFF’S GUIDES™ by clicking here

“The ultimate guilty pleasure book!”

—SAN ANTONIO EXPRESS-NEWS