This was excerpted from Ron Franscell’s DELIVERED FROM EVIL, a book that explores the lives of 10 ordinary people who survived mass killers. One of those monsters was a racist sniper named Mark Essex, who perched in a downtown New Orleans hotel in 1973 with an evil plan to kill as many white people as possible.

The private war of Mark James Essex began in the peaceful prairie town of Emporia, Kansas, an American Gothic village once described as “grassland, stoplights, grassland again.”

Emporia was a meat-packing town of fewer than thirty thousand citizens, but fewer than five hundred of them were black in the 1960s. “Jimmy” — as his friends and family called him — was the second of five children born to Nellie and Mark Henry Essex, a foreman at one of the local meat plants. The seven of them lived in a modest white frame house on the eastern edge of town, near the Santa Fe Railroad tracks, where most of the town’s minorities also lived.

Emporia was a meat-packing town of fewer than thirty thousand citizens, but fewer than five hundred of them were black in the 1960s. “Jimmy” — as his friends and family called him — was the second of five children born to Nellie and Mark Henry Essex, a foreman at one of the local meat plants. The seven of them lived in a modest white frame house on the eastern edge of town, near the Santa Fe Railroad tracks, where most of the town’s minorities also lived.

Jimmy grew up happy but soft-spoken, congenial but unremarkable. He was the kid nobody noticed and few remembered. He loved to fish and hunt, and he was a crack shot. He attended church faithfully enough that he talked about becoming a minister someday. He mowed neighbors’ lawns for pocket money. Jimmy Essex was, both literally and metaphorically, a Boy Scout and a choirboy, not a loner or rebel.

In school, Jimmy was a C student who probably had Bs in him, but he never pushed himself that hard. Short and skinny, he didn’t play sports, although he played saxophone in the Emporia Senior High School band for three years. When it appeared he was better with his hands than with his mind, Jimmy spent his last two years at a vocational-technical school, where he focused on auto mechanics.

In January 1969, after one listless semester at college and worried he might be drafted to fight in Vietnam, Jimmy Essex enlisted for four years in the United States Navy. After graduating from boot camp with outstanding ratings, he went to Dental Technician School, where he again graduated with the highest honors before being assigned to the clinic at the naval air station in Imperial Beach, California.

Jimmy wasn’t in Kansas anymore. Back home, he’d never seen racism as virulent as he saw in the Navy, where he came to believe black men were still treated as second-class citizens. He suffered racial slurs, ridiculous and meticulous searches of his car when he came and went from the base, harassment in the barracks, extra guard duty, trifling orders from white superiors intended only to exasperate — all irritations that most black sailors encountered but shrugged off.

But not Jimmy Essex.

Although only five-foot-four and under one hundred forty pounds, sometimes Jimmy fought back physically. Sometimes he complained bitterly to officers about the racist behavior he experienced. In letters home, he wrote that “blacks have trouble getting along here.” His constant skirmishing often landed him in trouble and marked him as a troublemaker.

Eventually, Jimmy befriended a black sailor named Rodney Frank, a convicted rapist and armed robber from New Orleans who hid behind his own militant bombast. Frank introduced Jimmy to radical Black Panther literature, to the revolutionary writings of Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton, and to Black Muslim fanatics off-base.

In a matter of months, everything changed. Jimmy Essex, the quiet choirboy from Kansas, was dead. Mark Essex, the angry revolutionary, stood defiantly in his place.

On October 19, 1970, Essex went AWOL. He packed a duffel bag and boarded a bus back home to Emporia. When his parents picked him up at the bus depot, he told them he’d come home “to think about what a black man has to do to survive.”

He was angry, bitter and isolated, obsessed with the wrongs he’d suffered and adamant about not returning to the Navy. His worried mother asked the Rev. W.A. Chambers, the Baptist minister who’d baptized Jimmy at age twelve, to speak to her son. Essex wanted to hear none of it. He was not only disillusioned with the world, but with God, too.

“Christianity is a white man’s religion,” he told his former minister, “and the white man’s been running things too long.”

Twenty-eight days later, Essex returned to his base to face a court-martial.

Although he had already pleaded guilty to being absent without leave, Essex’s defense was that the Navy’s entrenched racism was to blame. Hate made him do it. “I had to talk to some black people because I had begun to hate all white people. I was tired of going to white people and telling them my problems and not getting anything done about it.”

The court actually gave credence to Essex’s claims of discrimination and handed out a relatively insignificant sentence, but within weeks, Essex was given a special discharge for unspecified “character and behavior disorders” after a Navy psychiatrist had concluded that Essex had an “immature personality.” In his report, the psychiatrist noted that Essex exhibited no suicidal tendencies but “he alludes to the fact he ‘might do something’ if he doesn’t get what he wants.”

In the end, the Navy washed its hands of Seaman Mark James Essex, who served little more than half his enlistment.

Starting in February 1971, Essex spent a few months in New York City, where he voraciously consumed Black Panther Party propaganda and fueled the flames that were beginning to flicker deep inside. He studied the Panthers’ urban guerilla warfare tactics and started calling cops “pigs.” He also learned that one of the Panthers’ weapons of choice was the .44 Magnum semiautomatic carbine, a light and powerful hunting rifle that was devastating at close range.

Back in Emporia, Essex couldn’t adjust. His few childhood friends had all moved away, and he yearned to live in a black man’s city. He worked a series of odd jobs for a year or so but never with any enthusiasm. His hatred, though, continued to simmer.

Then one day, he walked into the local Montgomery Ward store and bought himself a .44 Magnum Ruger Deerslayer rifle, which he practiced firing in the countryside until the gun had become an extension of him.

Whether Emporia had become too claustrophobic or Essex had decided to launch a new front in his private race war, nobody knows. But in the summer of 1972, he picked up the phone, called his old friend Rodney Frank — also recently drummed out of the Navy as an incorrigible — and decided to move to New Orleans.

To the outside world, Mark Essex appeared to be just another young black man who didn’t know exactly where he was going or why. He entered a training program for vending-machine repairmen and rented a cheap apartment in the back of a shabby house.

But inwardly, he was reaching an ugly kind of critical mass. His defiant, revolutionary outlook grew darker. He began calling himself Mata, the Swahili word for a hunter’s bow. He was devouring militant newspapers and books. And he was filling every inch of the pale brown walls in his little two-room with a hateful scrawl of angry anti-white slogans like MY DEATH LIES IN THE BLOODY DEATH OF RACIST PIGS … POLITICAL POWER COMES FROM THE BARREL OF A GUN … HATE WHITE PEOPLE BEAST OF THE EARTH … KILL PIG NIXON AND ALL HIS RUNNING DOGS.

All references to whites — and that was most of them — were daubed in red paint. The rest were black. He even wrote on the ceiling, taunting the police he knew would eventually visit his frowzy sanctuary: “Only a pig would read shit on the ceiling.”

In November 1972, when Essex heard the news that two black students had been gunned down at Southern University while protesting the white man’s oppression, he declared his own personal war on whites and cops.

After Christmas, he hand-wrote a note to a local TV station announcing his bloody intentions:

Africa greets you. On Dec. 31, 1972, aprx. 11 pm, the downtown New Orleans Police Department will be attacked. Reason — many, but the death of two innocent brothers will be avenged. And many others.P.S. Tell pig Giarrusso the felony action squad ain’t shit. MATA

The attack happened as Essex had promised, although the letter was not opened at the TV station until days later. It was revealed too late to prevent the murders of Alfred Harrell and Ed Hosli. Nevertheless, it would not only link Mark Essex undeniably to those New Year’s Eve shootings — in which his first victim, ironically, was a black man — but foretold a bigger, bloodier butchery to come.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On the rain-shrouded morning of Sunday, January 7, 1973, Mark Essex girded for battle.

Almost a thousand miles away, his mother Nellie Essex prepared for church, where she would cry and pray for her son’s wayward soul.

Firefighter Tim Ursin kissed his children goodbye.

And a whole city awoke to a misty, gray day that would be unlike any before it.

Shortly after ten a.m., Mark Essex walked back into Joe Perniciaro’s market and stood in the doorway holding his .44 Magnum hunting rifle in his right hand. With his wounded left hand, he pointed at Perniciaro.

“You. You’re the one I want,” Essex shouted. “Come here.”

Perniciaro recognized him as the bandaged young man who bought the razor five days before and he started to run toward the back of the store. Essex, believing Perniciaro had fingered him to cops, had come for revenge.

Essex fired one booming shot — blasting a gaping hole in the grocer’s right shoulder and knocking him to the floor — before he turned and ran down the street.

Four blocks away, a fleeing Essex ran up to a black man sitting in front of his house in a beige-and-black 1968 Chevrolet Chevelle.

“Hi, brother, get out,” he told Albert.

“You crazy, man?”

Essex leveled his rifle at the stunned man’s head.

“I don’t want to kill you, brother. Just honkies,” he said calmly. “But I will kill you, too.”

Jumping into the car, Essex peeled out in the stolen Chevelle, sideswiping another vehicle before disappearing into traffic.

Police radios crackled with nearly simultaneous reports of a shooting and an armed carjacking in the Gert Town district. Cruisers scrambled to respond, but the stolen Chevelle eluded them. All they had was a description of a slim, young black male, up to five-foot-four, weighing about a hundred forty pounds, wearing a green camouflage jacket and olive-drab fatigue pants. He was carrying a hunting rifle onto which he’d tied a red, green and black handkerchief — later identified as the Black Liberation flag.

While police searched for the stolen Chevelle, Mark Essex careened into the parking garage of the Howard Johnson Hotel on Loyola Street and parked it on the fourth level. He ran up the stairwell to a locked fire door on the eighth floor, where he pounded until two black maids came to the door. He told one he wanted to visit a friend who was staying on the eighteenth floor.

She hesitated. She could lose her job if she let a stranger through the fire door.

“Are you a soul sister?” he asked one of them.

She said she was.

“Sister, the revolution is here,” he said. “It’s one for all and two for one.”

But the maid still wouldn’t let him enter, so Essex climbed another flight of stairs to the ninth floor, where he again pounded on the fire door and was again turned away by a maid.

On the eighteenth floor, he found a fire door propped open and went into the hallway, where he encountered two frightened maids and a houseman, all black.

“Don’t worry, I’m not going to hurt you black people,” he reassured them as he hurried past. “I want the whites.”

Civilians took cover in Essex’s rampage

But before Essex could get to an elevator, a white guest, twenty-seven-year-old Dr. Robert Steagall, saw him with the gun and tried to tackle him. They wrestled desperately for a few seconds before Essex shot the doctor in the chest. When Betty Steagall ran to her husband’s aid, Essex coolly put the muzzle of his carbine against the base of her skull and pulled the trigger. She died embracing her dead husband.

Essex untied the Black Liberation flag from his gun and threw it near their corpses.

Inside the Steagalls’ room, Essex set their drapes on fire and ran to the nearest stairwell.

Moving quickly throughout the hotel, he started several fires on various floors by soaking phone books with lighter fluid, then igniting them beneath the draperies. The whole time, he’d shoot at any white folks he saw and set off firecrackers in smoky halls and stairwells to create the illusion that many snipers and arsonists were prowling the hotel’s eighteen floors, killing at random.

On the eleventh floor, he shot the hotel’s assistant manager point-blank in the head, blowing most of it away. On the tenth floor, he mortally wounded the general manager. On the eighth-floor patio, a gut-shot hotel guest floated in the hotel pool for two hours, playing dead.

On the eighth floor, Essex heard sirens outside. From the balcony of one room, he saw a firefighter scrambling up an aerial ladder toward hysterical guests on the floor above. He took careful aim and squeezed the trigger, hitting the fireman. He racked another cartridge into the chamber and took aim again, but the gun didn’t fire. He didn’t have time for another shot. Cops on the ground were firing back, so he ducked for cover.

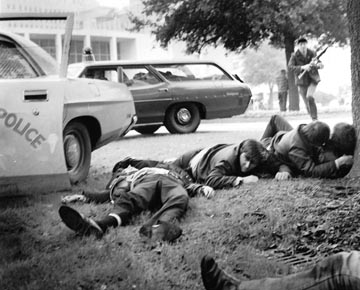

By eleven a.m., less than a half hour after Mark Essex laid siege to the Howard Johnson, police had set up a command center in the lobby, and hundreds of police surrounded the hotel. Sharpshooters had taken positions atop nearby buildings while other cops tried to keep curious onlookers out of the line of fire.

But it was fruitless. Local TV stations were going live, and their feeds were being picked up by networks for wall-to-wall coverage. Mark Essex’s war was being televised. Worse, word was leaking out that the snipers were militant black revolutionaries, and many angry African-Americans were gathering on the street outside the Howard Johnson to “Right on!” and “Kill the Pigs!” every time shots were fired from the balconies above.

From his perch on the eighth floor, Essex began to pick off cops who were scurrying in the streets below. One after another, they were falling wounded and dead.