“Reminiscent of Charles Frazier’s ‘Cold Mountain’ … Ron Franscell’s themes involve a fresh

approach to our rural roots as a font for the elusive American spirit.” — USA Today

Twenty-five years ago today, my first book—a literary novel called “Angel Fire”—was published.

Nobody out there was waiting for this debut fiction by an unknown scribbler from one of those squarish states out West, published by a small house down South the New York Times didn’t recognize. The day was quiet.

I loved the story but couldn’t know if anyone else would. Twenty-four years after war correspondent Daniel McLeod is killed in a Viet Cong ambush, his only brother Cassidy is mysteriously drawn to their Wyoming hometown, where he must confront a lifetime of his own ghosts. In the end, their story is about how we seek equilibrium, a delicate balance between memory and the unknown, dislocation and homecoming, loss and restoration. It also resonates with the rhythms of small town life, the blessings of memory, and the pain of loss.

I loved the story but couldn’t know if anyone else would. Twenty-four years after war correspondent Daniel McLeod is killed in a Viet Cong ambush, his only brother Cassidy is mysteriously drawn to their Wyoming hometown, where he must confront a lifetime of his own ghosts. In the end, their story is about how we seek equilibrium, a delicate balance between memory and the unknown, dislocation and homecoming, loss and restoration. It also resonates with the rhythms of small town life, the blessings of memory, and the pain of loss.

But as “Angel Fire” seeped into the American consciousness over the coming months, it took on a life of its own. Flannery O’Connor Prize-winner Melissa Pritchard had called it “an important story of mythical proportions.” USA Today praised its evocative, timeless themes and made it a bestseller; Library Journal invoked the poetic spirit of Robert Olen Butler. It inspired the visuals for a popular music video. The story I carried around in my head for 15 years won the Wyoming Literary Fellowship and became part of several colleges’ American literature curriculum, even dissected in a handful of master’s theses.

Ron Howard’s Imagine Entertainment flirted with the book for a long time before passing, and it was ultimately optioned twice by an independent producer who could never get a greenlight—but people were reading “Angel Fire.”

Then in a moment even an eager young novelist could not have imagined, the San Francisco Chronicle listed “Angel Fire” among its 100 Best Novels of the 20th Century West, tucked at No. 74 between Thomas Berger’s “Little Big Man” and Louise Erdrich’s “Love Medicine.”

Early on, one book critic said “Angel Fire” felt like a deeper, more timeless story, even though it was just a contemporary American novel about a couple brothers. It drew its familiar rhythms from many sources: The Bible, various cultural mythologies, frontier and Native American lore, and my own imagination. The book contains references to contemporary American legendary figures, from Cannibal Phil Gardner to John Wayne, and it introduces new stories with the patina of local myth: Moses the itinerant ball player, the false legends of Fakey Ducas, Flashlight Freddy Bascombe, the wandering gandy-dancer Pledger Moon, and the reluctant icon Jack Lazarus.

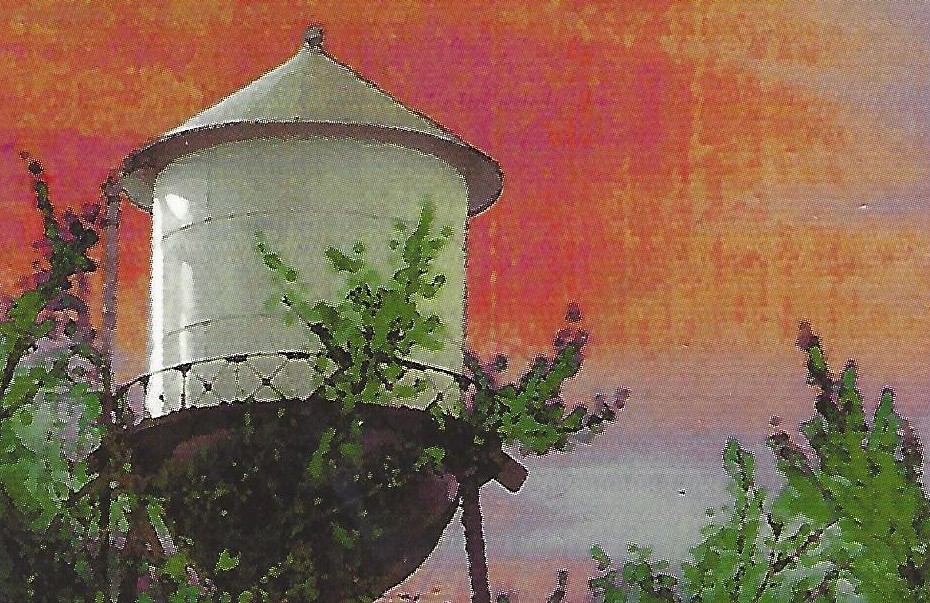

Almost anybody who has lived in a very small town will recognize the archetypal elements of West Canaan, Wyoming: The water tower, the evening whistle, the cemetery, the colorful, unorthodox characters, and their stories. But in “Angel Fire,” these also recall archetypal mythical symbols: The water tower is the lofty and eternal center of our young heroes’ universe. The evening whistle literally sings the siren’s song that draws Daniel home to his final struggle.

Author photo, 1998

Why? If myths endure because of familiar rhythms that transcend cultures and centuries, I wanted “Angel Fire” to feel familiar to a reader, perhaps at a subconscious level. I felt it would give the story a complex subtext, without harming its beautiful simplicity.

“This book has been a favorite of mine since I first read it,” says Wyoming bookseller Vicki Burger, “and I have enjoyed sharing it with many, many customers over the years.

“It is a tale of the bonds of family, where we go when the world has become too much and we need strength and comfort,” Burger says. “We go where we find our memories, our foundation but that, too, has a price.”

She quotes a poignant “Angel Fire” line from memory: “Pain is the price we pay for memory. It’s some kind of sin to forget what hurts, as much as it is to forget what makes you smile. Suffering has its meaning, and memory has its graces.”

“Those words have stayed with me over the years and are no less poignant or true today, Burger says. “This is a novel to be savored and returned to time and again.”

But the beauty of “Angel Fire” is that it tells a timely contemporary story all its own. Strip away the mythological subtext and it remains a haunting story about two brothers who have detoured around their personal pain for so long that they’ve become lost, and they must find their way back before they can be made whole again.

“Angel Fire” is a house with 100 secret rooms. You are free to wander through this magnificent place and open any doors your wish, but you won’t find every secret room. I’m not entirely certain whether I can find them myself anymore. Today, it’s out-of-print but still available in ebook, audio, and used editions.

I’m comfortable knowing there will be some mystery about this story long after I’m dust.