My father-son memoir The Sourtoe Cocktail Club, about our Yukon odyssey to the literal edge of the Earth to find a cocktail containing a mummified human toe, was published in 2011. It is a deep—and often funny—contemplation about whether I was still relevant to my teenage son after a divorce. On Father’s Day, it seems appropriate to contemplate it again. Here’s an excerpt:

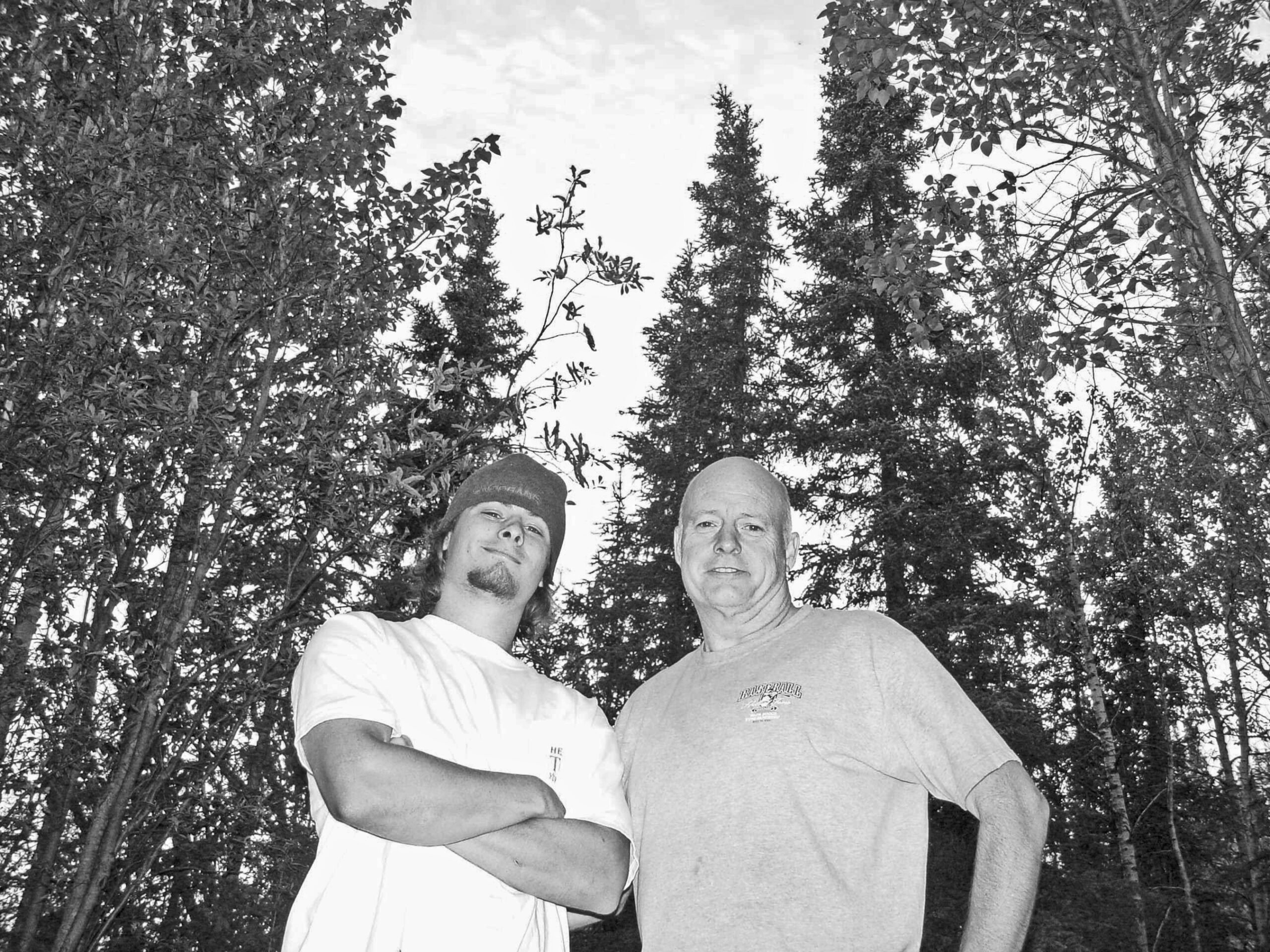

Ron and Matt above the Arctic Circle, 2007

Before there were roads, there were rivers. The shortest distance between two points might be a straight line, but water finds the easiest route. And explorers like Lewis and Clark knew this as they traversed this country in search of a distant sea. They followed the Musselshell River in Montana.

She rises in the Crazy Mountains, gathers herself below the treeline, trickles across wildflower meadows, cuts through deer trails and timberfalls, warms her icy blood in the early-morning sun that paints the eastern slope of the Crazies. Sometimes in spring, warm air from the basin often seeps up the canyons and cools over the cold water, congealing in a “Cheyenne fog” that drapes the boulders and the trails and the trees and the graceful shadows of brown trout just below the surface.

Down in the otherwise treeless flats and pleated badlands, she snakes slowly east and north, absorbing whatever intermittent tributaries with names like Haymaker and Ninemile have to offer. And, true to the habits of rivers and men, she chooses every easiest inch toward the Missouri, the Mississippi and the Great Water.

I touch Matt’s leg and point to the barbed wire fence in the barrow pit.

“Red-winged blackbird,” I say.

Matt says nothing, but I’m absorbed in the accordion folds of a life-imitates-art-imitating-life moment.

“That’s just a cool coincidence. Just like that book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. The guy and his son go on the road. On the first page, they see a red-winged blackbird …”

“Never read it,” Matt says.

“It’s a true story. There’s a lot of philosophical crap, deep hoo-haw about romance and rationale, but this father went crazy once and had shock treatment and he’s worried his son might go crazy, too, so they get on a motorcycle and head across Montana to California.”

“To see blackbirds?”

“No. Just to … I don’t know. Make sure …”

“Of what?”

“You know, father and son stuff. That they didn’t lose each other. That they shared one thing that nobody else shares. That … I don’t know … that nothing could come between them.”

I am shoveling smoke here. Worse, I am tangled up in those discordant accordion folds, not sure if I’m talking about the book or us.

“What happened in the end?”

“The guy comes to the conclusion that life is complicated and that might be because we have confused what we are and what we do, and so there’s this metaphysical …”

“No, dad,” Matt interrupts, “I mean with the guy and the kid.”

“Oh, I think they come to a big cliff, nobody jumps, then go back home and live happily ever after,” I say. “Well, not exactly. I guess the kid grew up after the book came out and got stabbed to death by a mugger.”

Matt studies my face for the tell-tale twinkle in my eye or the slight lilt at the corner of my mouth that always gives my lame jokes away, but it was true.

“You serious? That sucks,” he says.

We go for a long time without talking. Not even Sydney, the disembodied GPS girl, has anything to say on this long, straight highway. Matt watches the patchwork of pasture and prairie pass, and sips his Rock Star energy drink. I know he’s thinking about dying now. Not the messiness of it, but more the abstraction of it. He is old enough to see through the delusion of immortality, young enough to still find romance in death.

Or maybe not.

Maybe that’s one of the reasons a father and a son embark on a long journey together, to strike a balance between death and immortality.

Maybe that’s one of the reasons a father and a son embark on a long journey together, to strike a balance between death and immortality.

Or maybe not, again.

“Is it deep?” Matt asks.

“The book?”

Matt rolls his eyes.

“The river.”

“Not really. Wider than it is deep. And slow.”

“I haven’t really been fishing since that time we went to the creek in Colorado,” he says.

God, I want to stop, right here, right now, and take my son to the river.

“If I had my gear, we’d go,” I say. “Maybe in Canada …”

I am not a graceful fisherman, but I draw no distinctions between time and trout streams. Every excursion is more a place than a measure of a year, and every stream flows through days, through me. I know fishing is about patience, which, like hope, is really just another way of describing the passage of time. I am not as patient as I imagine great fishermen to be, but I am getting better … I just want to get better faster.

My grandfather Joe taught me to fish. He was my stepfather’s father. For a long time I didn’t know we weren’t blood-related, and after that, it just didn’t matter. Giuseppe Pietro Franscella voyaged alone from his small Italian village to Ellis Island when he was just seventeen. With twenty-five bucks in his pocket, he caught a train to San Francisco — where, in his zeal to be an American, he renamed himself Joseph Peter and shed the “a” in his surname as if it were all that shackled him to the Old Country. Forty-six years later, when my mother married his son, he was an ordinary Joe.

Long before I came along, Joe had been a big-time chef in Hollywood’s rococo-swank Alexandria Hotel and the glamorous Ambassador, where he met silent movie stars like Valentino and Nazimova, a Russian actress with whom he was curiously taken.

My grandfather was the proto-Bourdain: profane, adventurous, street-smart, intensely honest, tough and a good cook. He always claimed he could sleep anywhere “like a badger,” because, well, he must have respected badgers’ toughness or sleep habits. After he retired, he often made breakfast for the visiting grandchildren, and it might be silky oatmeal, French crepes — or eggs scrambled with calf brains. He could also cuss in several languages. He was the first adult I ever heard say “fuck,” but his favorite invective was “crap,” whose “r” was chopped and diced by this cantankerous Italian chef until it unzipped more like “krrrep.” For a long time, I didn’t even know “krrrep” was English.

He didn’t just tell other people’s stories. He lived his own stories, and they were good stories.