Every crime writer has heard this little heckling voice, usually from the cheap seats, but sometimes from inside his own head. It isn’t always loud, but it’s often piercing.

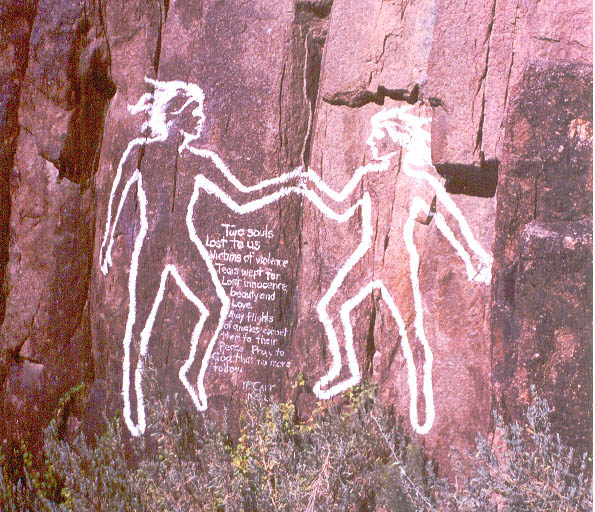

Tragically, today is the 43rd anniversary of a monstrous crime against two of my childhood friends in the small town where we grew up: Two young sisters were abducted by career criminals, terrorized through the night, then came a rape before they were thrown from a very high bridge in a remote spot. One died, one lived … and the town was shaken so thoroughly in the aftermath that it still echoes there today, more than 40 years later.

I grew up to write a bestselling book about it. The Darkest Night enjoyed a revival on bestseller lists when its long-awaited digital edition was released last year. With more than 125,000 copies in print, this intimate story has struck a chord with American readers for more than eight years … and it has also struck a nerve.

“Someone profiting from this tragedy is inexcusable!” somebody named Eric posted at Facebook. Although he admitted he probably wouldn’t read The Darkest Night, he swiftly deemed it as greedy, exploitive, and parasitic.

“Eff’in money grubbers! I beg you to use part of the profits to support something good for

children! Back ‘Amber Alerts,’ donate to build a safe playground for disabled children, but do it yourself! Don’t just write a check and call it good! And I hope you carry the guilt that the money is coming from the loss of two, yes two, innocent lives lost!”

So days such as this, when I am counting the losses and assessing whether it was a story worth telling, I listen to many voices. But I hear those voices, too.

Crime writers have heard this discordant grousing since Truman Capote wrote about the slaughter of an innocent farm family in In Cold Blood. Vincent Bugliosi heard it after Helter Skelter graphically exposed Manson as a bogeyman for the ages. Ann Rule heard it after every #1 New York Times bestseller she’d written.

Victims Becky Thomson (right) and Amy Burridge (foreground) with their mom

It reflects our sense of justice: Victims should profit. Not killers, not cops, not authors or filmmakers, not newspapers or TV stations. Only victims, once and future.

Eric’s discomfort is a common challenge for crime writers. A lot of people like Eric (including me) think a story should improve society, starting with the innocent victims of a crime. We simply disagree about the power of storytelling to improve society (and we likely have vastly different ideas of just how much an author profits from a book).

.Journalists tell stories, good and bad. Authors enlarge the experience of a society. They have a sense of justice, too, or they probably wouldn’t be telling these stories. And I must admit that there are a few—a very few—writers and publishers who exploit human tragedy purely for personal gain. But

I wouldn’t write crime stories if I thought they couldn’t change us for the better.

The alternative is that such tragedies are never committed to the culture’s memory in a book, story, or movie. If not for books like The Darkest Night, the memories of these victims would be lost or confined to only a small community. A powerful story is shared by everyone.

The stories we have retold through time haven’t always ended well, but it’s the endings that always decide whether a story is worth retelling—even a sordid, sad crime story in which all the wrong people die.

So the best thing I could do for the victims in this case was share the story so more people know them, and more people are energized to prevent it from ever happening again. To kick-start that energy, I donated every dollar of The Darkest Night’s first-day sales to local national chapters of Parents of Murdered Children in the names of my two childhood friends and next-door neighbors, Amy Burridge and Becky Thomson. But that, too, was merely to soothe the heckler in my own heart, who reminded me that this might never have been my story anyway. I just told it.

Nevertheless, a lot of people do jobs that are distasteful, either for the greater good or because we don’t want to do them ourselves. Should a gravedigger or florist work free just because death has created a need for his labor? Should a surgeon work for free because someone will die if he doesn’t?

Conversely, some people get paid for work that is, at its heart, good, altruistic, and humanitarian. Should teachers, cops, firefighters, pastors, and nurses work for free simply because nobody should profit from good deeds?

Whatever money an author (or newspaper or filmmaker) earns merely makes it possible to continue telling stories. If they are valuable to us, more can be written. If they exploit or erode our culture, I like to think they’ll die out (but reality TV tells me I might be wrong).

I believe deeply in the power of a story to improve society. I believe artists of all kinds are undervalued in our culture, which too often believes an artist’s contributions should be freely given. And I think the way we enhance our existence is through stories, so we mustn’t make it impossible for storytellers to sustain themselves.